Cold Winter Deserts of Turan

Even in ancient times, the region of Turan was seen as an enigmatic land, referenced in Persian mythology as a vast and mysterious realm beyond the borders of the empire. With stark dramatic landscapes that can sometimes seem otherworldly, it's an extreme desert region that, at first glance, appears uninhabitable except for the most unusual forms of life. But the features of cold winter deserts that once fascinated ancient civilisations have since been explained by modern researchers as incredible examples of how the natural world will find ways to survive.

Cold winter deserts are very rare across the world. There are small patches of them in the Great Basin and Sonora in North America, as well as in Patagonia in South America. But the vast majority of them are in Central Asia, stretching across an enormous swathe of land from the Caspian Sea in the west to the Turanian high mountain ranges in the east. In total, they cover more than 80 per cent of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, and almost half of Kazakhstan.

To protect and give access to a range of ecosystems within the deserts, 14 specific components have been chosen to make up the World Heritage listing, with some of them grouped together in clusters. There are two clusters in Kazakhstan – Altyn-Emel and Barsakelmes; three clusters or components in Turkmenistan – Bereketli Garagum, Gaplangyr, and East Garagum; and two clusters or components in Uzbekistan – Northern Ustyurt and Southern Ustyurt.

One of the first things you'll notice when you visit the deserts is how arid they are. There is virtually no rain at all during summer and autumn, while during the rest of the year the annual rainfall is still generally less than 250mm and often as little as 100mm (equivalent to just one average month in New York City, for comparison). Along with the dryness, the extreme temperatures have the biggest effect on the environment. In winter it can be as cold as -45°C (-49°F) and in summer it can reach 50°C (122°F).

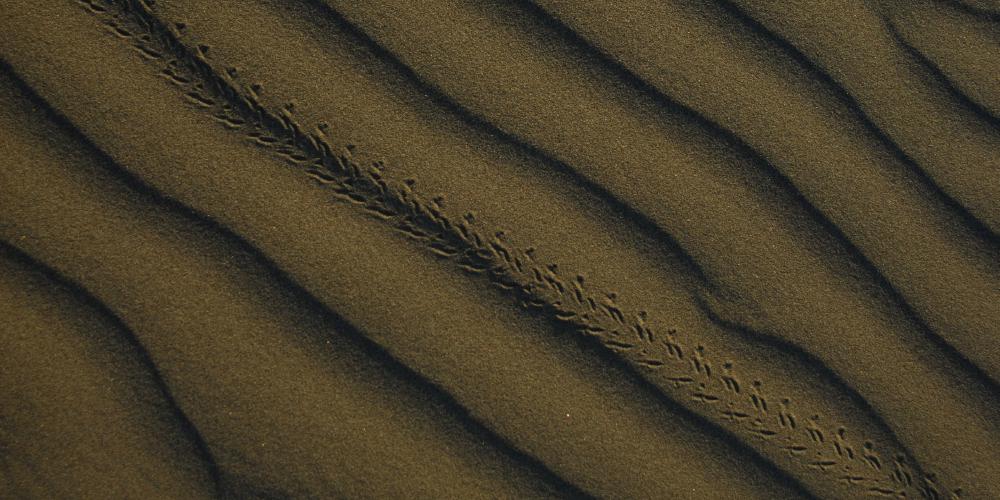

Because the desert coverage spans a distance of about 1500 kilometres from east to west, there's a remarkable diversity in the types of landscapes you'll find in the various protected areas of the Turan region. The winds reign supreme in the sandy deserts, sculpting rolling dunes and blowing grains onto fixed hills with sparse vegetation. In the clay deserts, the earth cracks during the warmer months and shimmers on its salty crust. There are stony deserts with rugged rocky landscapes dominated by dramatic cliffs that have just a few plants clinging to crevices. And in the loess deserts, the fine dust particles that have accumulated over millennia create a soft plateau-like terrain that offers more opportunities for vegetation like grasses and small trees to grow.

While most of the desert varieties have sparse flora, there are species that have evolved to be able to withstand the extreme conditions. They've adapted with techniques like reducing the number of leaves to conserve water, growing their roots deeper to reach underground water reserves, and forming woody sprouts to provide more support from the wind. Because they've morphed due to the unique conditions here, many of these species can't be found anywhere else in the world, so seeing them for yourself is a fascinating and unique experience.

A life of extremes

It's not just plant life that has evolved within the environments of the Cold Winter Deserts of Turan. In response to the severe temperature changes and the lack of water, there are also many animal species that have developed their own survival strategies over the years, adapting in remarkable ways. Spotting some of this wildlife is likely to be a highlight of your visit to the national parks and reserves that make up the World Heritage Property.

Some of the ways animals have evolved to live in the deserts are physical. For instance, there are insects that have developed special exoskeletons that prevent them from drying out; some lizards have adapted to grow thicker skin for better insulation; and there are mammals have denser fur to keep warm air next to their skin, such as the honey badger, sand cat, and marbled polecat, which all have special conservation interest.

There are also physiological ways that animals have adapted, developing tolerance of tissue to high temperatures, as well as tolerance to cold and tolerance to dehydration, or perhaps having forms of water storage or ectopic fat storage. An interesting example of a physiological technique found here is 'adaptive heterothermy', which means an animal can change its body temperature throughout the year to better match the air temperature that it finds itself in.

And then there are also behavioural changes that you can see, in particular migration. There are a large number of species that move throughout the year to find more suitable conditions – so many, in fact, that the region has been dubbed 'the Serengeti of the North'. Some of the most significant migrating animals that you may see are the goitered gazelle, the kulan, the saiga antelope, and the urial, all of which are threatened to some degree. Of course, there are other animals that deal with the severe change in temperatures not by moving, but by taking refuge in burrows or beneath the sand.

For birdwatchers, the cold deserts of Turan offer a myriad of opportunities to see distinctive and rare species, with many birds resident to the protected areas, while others rest on their migrations during the year. Across the World Heritage Property, there are 15 near threatened species, 10 vulnerable, 5 endangered, and two critically endangered (the Siberian crane and the sociable lapwing). Globally threatened species that can be seen here during the whole year include the Asian houbara and the great bastard. And two interesting endemic birds with features related to the cold deserts are the Turkestan ground jay and the Asian desert sparrow.

Often remote and untamed, these cold winter deserts are an adventure even for the most intrepid travellers. By car, horseback, or even by foot, exploring the intense scenery is just the beginning. As you see more of these unique ecosystems, you'll be able to spot some of the threatened species of wildlife that have adapted to the extreme conditions, an incredible face-to-face demonstration of nature's ability to survive.