Epidaurus revisited and the history of health, by Vasileios Lambrinoudakis

The Epidaurian cult started in the 3rd millennium B.C. on a hill to the east of the plain in which the sanctuary of Asclepius was later founded. Abundant springs of healthy water attracted a family of rich landowners, to settle near the precious water (Figure 1). The settlers lived there for several generations before moving elsewhere— yet leaving elements of their heritage: The founders of the settlement were buried there in three tombs and were venerated as community forefathers.

As time passed, they became the hero-founders of a whole group of affiliated communities that settled in the region. Then, sometime in the early second millennium B.C., the place became a shrine. The blessing emanating from the tombs of the hero founders was believed to bestow health and welfare to their descendants, which was the first step for a cult of health.

The hero founders merged then with fertility gods of the region—at that time, a goddess of fertility (Figure 2), perhaps with an acolyte who later became Apollo. The protection of forefathers was now replaced by divine help, which was invoked through a primitive, magical process. Worshippers purified themselves with spring water before invoking the deity. Then, an animal was sacrificed and its flesh consumed on the spot in the imagined presence of the deity, who was invited to participate in the ritual meal and offered a portion of the meat. This procedure was a kind of sacred communion. By eating the same blessed food that strengthens the god, acolytes received divine life and health-sustaining nourishment. The process is documented by the architectural remnants and artefacts found in the sanctuary, which consisted of an open-air altar, on which the burnt ashes of victims accumulated, a big terrace on which the ritual meals took place, and a small chapel where the instruments of the cult were kept.

Without interruption, the sanctuary developed in the early years of the 1st millennium as the official religious centre of the Greek city-state of Epidaurus. The male acolyte of the prehistoric goddess became the Greek god Apollo (Figure 3), who had associations with medicine. The main ritual of the cult, the communion of divine food, continued, and the sanctuary flourished again during the 7th and 6th century B.C. Rich votive material found in the excavations testifies to the long lasting prestige of the cult.

By the 7th century B.C., the old sanctuary could not accommodate the crowd of visitors it attracted. This led to the transplantation of the cult a few hundred meters westwards in the plain, at the foot of the hill on which the old sanctuary lay (Figure 4.). Here Apollo was escorted by another healer hero, Asclepius (Figure 5), venerated by the predorian population of the country, who now, albeit keeping his chthonic character, was raised to the level of a god and became the son of Apollo. From that time to the end of antiquity the old and the new sanctuary functioned as a twin cult, belonging to Apollo and Asclepius.

In the new sanctuary two different healing treatments, both originally magical, were combined: The traditional way of achieving health, through sacrifice, ritual meal and communion, continued in the name of Apollo and Asclepius. An ash altar in the heart of the new sanctuary, incorporated later in a building to host this ritual, received the bloody sacrifices. A second procedure, aiming directly—albeit always magically—to cure, was introduced together with Asclepius in the new sanctuary. This was the incubation, the cure obtained in a meeting with the healing god in a dream. The patient slept on the ground in order to see the god in a dream. The god healed him either by operation or by giving him a drug, or suggesting a cure, or even sending a sacred animal to do the work.

To understand the meaning of this procedure, we must briefly analyse the nature of Asclepius. He developed as a god out of a hero. Heroes were usually born by a god and a mortal, so they had the supernatural power of the divine—yet they shared the nature of mortals, bound with death and regeneration. So they were bound with the earth, which receives everything worn out and produces new life. Asclepius, as all heroes, was a chthonic power. He had the regenerating power of earth, as explained in the myth of his creation.

Immediately after he was born, Asclepius began to cure people. He even resurrected some of them. Hades, god of the Underworld—being afraid that this activity would empty his realm—complained to Zeus, who hit Asclepius with his thunderbolt and buried him in the earth. When Apollo complained about his son, Zeus found a solution. Asclepius would continue to live, but he had to live underground, and from there he was allowed to continue healing people.

So sleep, during which the patient met the god and awakening, was a simulation of death, of descent to the Underworld and of regeneration. Incorporating the regenerating power of earth, Asclepius absorbed the illness menacing the patient, the illness, and sent him vital again awakening into daylight. These beliefs are well documented in the sanctuary. Greeks personified Sleep and Death and considered them as brothers. In the sanctuary of Epidaurus, Hypnos was venerated together with Asclepius in a special shrine as Theoi Epidotai, which means gods bestowing goods to man.

The magic practices aiming to obtain health continued to function in the sanctuary to the end of the ancient religion. The monumental buildings with which the sacred space was embellished since the 4th c. B.C. served the same rituals. The ash altar was incorporated in a complex building with stoas accommodating worshipers participating in the ritual meal around the altar (Figure 6).

Since approximately 300 B.C., a huge building, a banquet hall, housed the ritual dining (Figure 7). In its rooms the bulk of the beds are preserved, on which reclining worshipers ate their meals. A monumental stoa was built for the incubation (Figure 8). Its eastern part was a ground-floor building, while its western part was two-storeyed. In the former, in which a sacred well was incorporated, patients prepared themselves to meet the god with purification, fasting, and reading of miracles, which were written on big slabs mounted at the walls of the building.

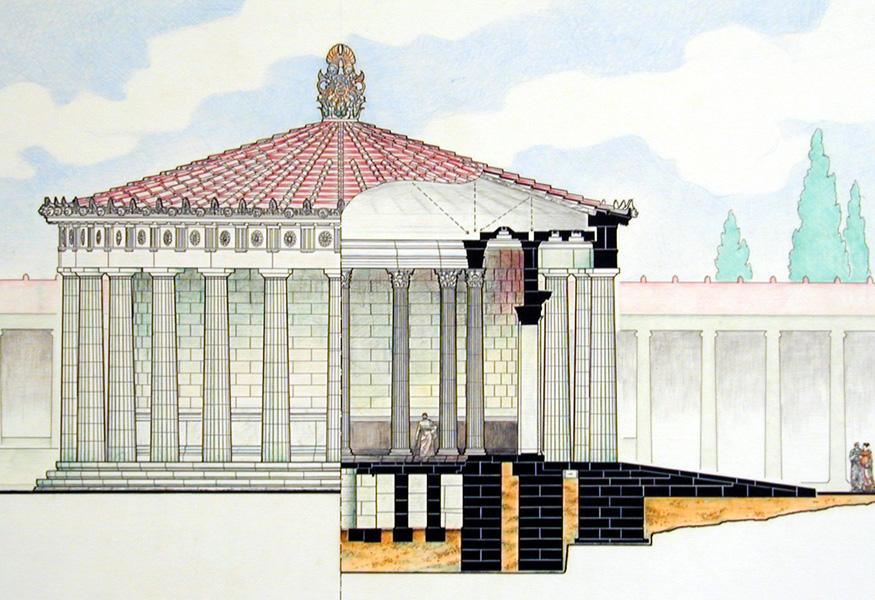

After this preparation, they went to sleep in the basement of the western part of the dormitory, expecting to be visited by the healer god. Immediately south of the Dormitory an elegant circular building characterised as Thymele (altar) or Tholos (vault) housed Asclepius in his chthonic character—made tangible by an underground part of the building containing meandering corridors imitating the dark passages to Hades (Figure 9). Ancient writers referred to it as the tomb of the god. This building and the dormitory were designed together to complement each other. The ceiling of the underground part of the Tholos lay exactly on the same level as that of the basement of the nearby dormitory. So the patient was meant to meet the god in his underground salutary space.

But in these magic procedures, not everything was left in the hands of god. His priests were called “servants of the god” (Figure 10). The experience acquired by them through close observation of diseases, symptoms, and recoveries attributed to the god, was transmitted and enlarged from generation to generation. The seemingly miraculous stories exposed in the dormitory allude to real medical treatment. The skilled human intervention is abundantly documented through evidence found in and around the sanctuary.

The use of medical instruments and vases for drugs is there attested at the latest since the fourth century B.C. (Figures 11 and 12). And after two centuries families of professional doctors, working scientifically outside the sanctuary are attested in Epidaurus. A well preserved tomb of such a family was unearthed in the outskirts of the ancient city, where one entered the road leading to the sanctuary. The tomb contained three sarcophagi belonging to doctors of three successive generations from the 1st to the 2nd century A.D. Some of their medical tools were buried with them.

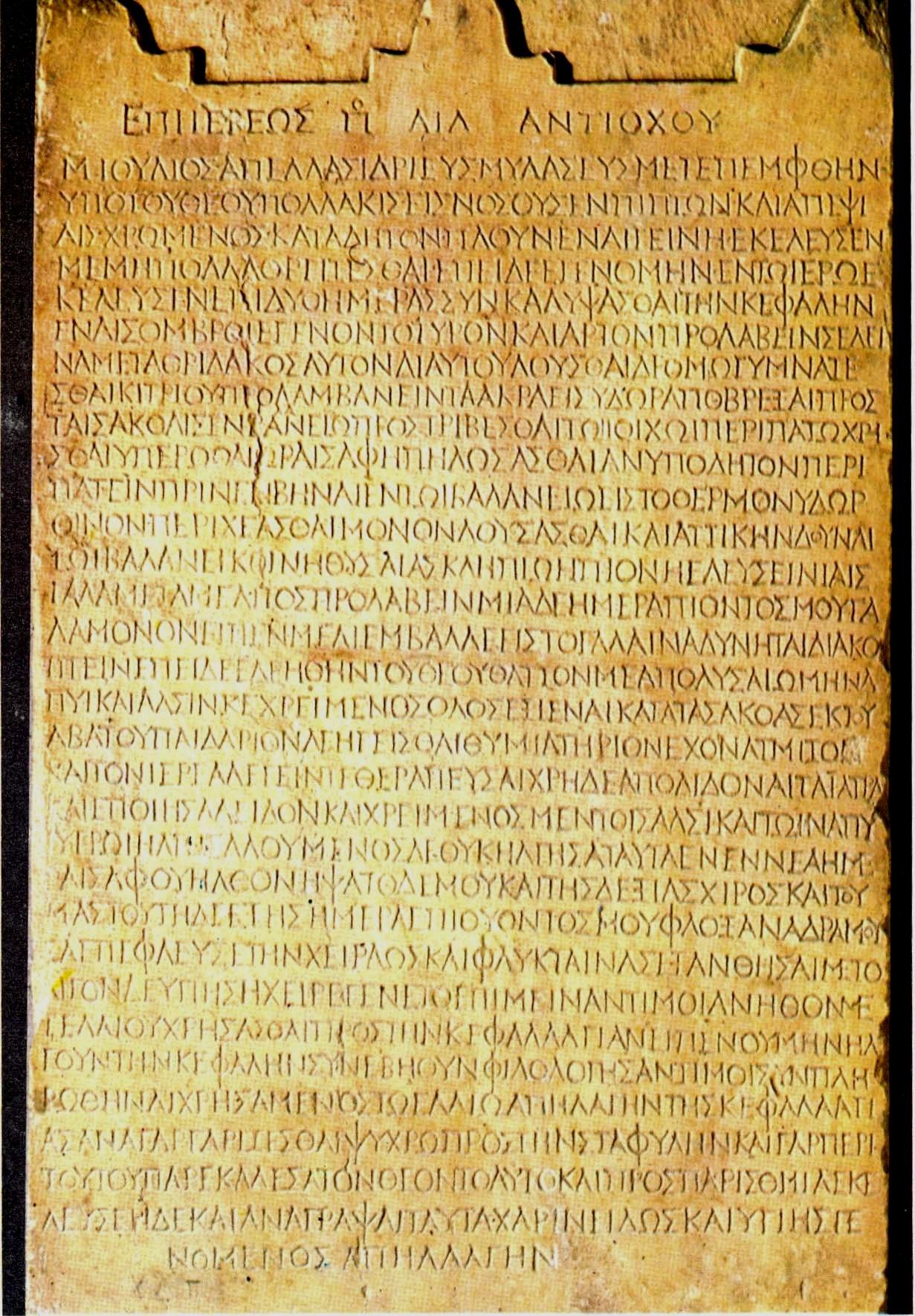

Although it was primarily attributed to incubation and divine help, medical care at the Sanctuary evolved into effective forms of medical treatment. An example of the new methods is found in the text of a sickly resident from Asia Minor of the second century A.D., Marcus Julius Apellas, who expressed his gratitude to Asclepius for being completely healed in Epidaurus (Figure 13). In his dream, the god prescribed a real medical treatment, including a diet of bread, cheese, celery, lettuce and slices of lemon, as well as coatings with mustard and salt, baths, athletic exercise and study in the library. Surgical treatment is also mentioned in later inscriptions.

The fame and influence of the Epidaurian sanctuary in matters of health became so renowned, that, beginning in the late 5th century B.C., the therapeutic cult of Asclepius spread across the Mediterranean. His sanctuaries in Athens, Pergamon and Rome are some of the most important early foundations of Epidaurus.

This is a brief version of the long story of Epidaurus as we know it today. Apart from its crucial contribution to the development of medicine, its pious legacy continued to go through the care of health in the Christian era, in parallel to scientific medicine. In Epidaurus, one of the largest early churches was built on the ruins of the sanctuary devoted to Saint John the Faster, who can cleanse and cure through fasting. And on the island of Tiber in Rome, a hospital still functions on the ancient ruins belonging to the religious order of Fatebene Fratelli, whose name reminds us of the "gods bestowing gods to man", venerated in the ancient sanctuary of Epidaurus.